Five Greco-Roman Myths That Christians Can Learn From

As an English professor whose spiritual growth has often been challenged and enhanced more by Greek mythology than by Christian devotionals, I am pleased that a growing number of Christians, especially among my fellow Evangelicals, are realizing that it is not a bad thing for Christians, whether old or young, to read and enjoy Greco-Roman myths. I am doubly pleased that many among that number are accepting something even more shocking: that Christians can actually learn from pagan mythology good and true things that possess real and eternal value. I would like to illustrate that claim by looking briefly at five myths that fall into three categories.

Why Are Things the Way They Are?

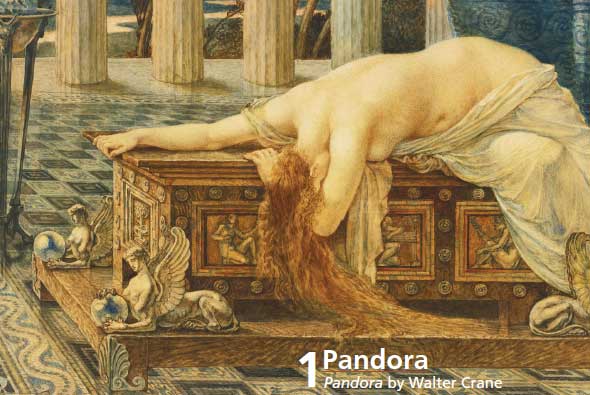

The annals of Greek mythology have preserved for us two tales that complement rather than repeat one another. They are both well known and have entered our language with such force that they have become a part of cultural literacy in the Western world. The first is the story of the first woman, Pandora. After showering on her all the gifts of beauty, grace, and skill (Pandora means "all gifts" in Greek), the gods placed in her hands a small box which she was warned never to open. At first, she heeded the gods, but after some time passed, her curiosity got the better of her, and she cracked open the lid to peer inside. Immediately, the top sprang open, and all the evils of the world—sin, war, disease, famine—flew into the air and distributed themselves across the face of the earth.

Pandora quickly shut the lid, but it was too late. The damage had been done and could not be reversed. She almost gave up in despair, when she heard a small voice at the bottom of the box call out to her to be released. That voice belonged to hope, and with it there came a faint promise that the evils she had released would not consume the human race.

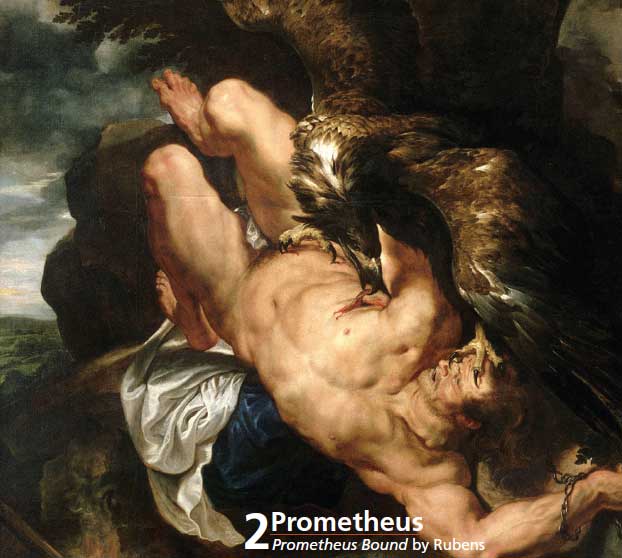

The second tale concerns Pandora's brother-in-law, Prometheus. Though a god himself, Prometheus felt great pity and sympathy for mankind, who had been kept in groveling fear by Zeus. In order to help man grow to his full potential, Prometheus stole from Zeus the secret of fire and gifted it to man. In retaliation, Zeus had Prometheus chained to a rock high in the Caucasus Mountains. Every morning, a ravenous eagle came and tore out his liver. Every night, the liver grew back, only to be devoured again when morning returned. Eventually, Zeus and Prometheus were reconciled, but Prometheus suffered greatly for his theft of the fire of the gods.

Taken together, these two timeless tales point to the biblical story of the Fall. Eve, like Pandora, was the first woman created by God. She was perfect in all ways, but she fell prey to the temptation presented by the serpent and disobeyed the one divine command that had been placed upon her. On account of that act of disobedience, sin was ushered into the world—though, with that sin, came a promise of hope. Even as God cursed Adam and Eve, he promised (Genesis 3:15) that one day the seed of Eve (Christ) would crush the seed of the serpent (Satan).

This mixture of sin and hope, of the plucking of forbidden fruit and the promise of restoration is also found in the Prometheus myth. This time, however, Prometheus takes on the roles of both Adam and Christ. He is like the first Adam, for he ushers forbidden knowledge (fire) into the world; he is like the Second Adam (Christ), for he suffers on behalf of man—a suffering that leads in the end to divine reconciliation.

Although we only need to know the story from Genesis 3 to understand the nature of the Fall, a knowledge of the myths of Pandora and Prometheus can help us understand, and even experience, some of the strange paradoxes that lie at the core of our fallen world and our fallen selves. It will help us to ask questions we might not have asked before: When is curiosity a good thing and when is it a bad thing? How does the bad kind of curiosity reveal a lack of trust in God? In gifting man with fire, did Prometheus play the role of a hero or of a villain, a savior or a rebel? Is knowledge an absolute good, or can too much knowledge be a bad thing? Why would God create us with a desire to know, and then punish us for plucking the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil?

The ancient Greeks who fashioned the myths of Pandora and Prometheus lacked access to the special revelation contained in Genesis and the Gospels, but they were aware that they were living in a world that was broken in some way and that they themselves were also broken. They also knew intuitively that there was a link between that brokenness and a fatal decision predicated on disobedience and a bad form of curiosity.

How Then Should We Live?

Mythology, then, sheds some light on why we live in a broken world, and why pain and suffering are rife. But those are not the only lessons it can teach the discerning Christian. The ancient tales of gods and heroes also offer sound advice on how best to live in such a world. Long before Aristotle defined virtue as the mean between the extremes, the myth-makers of the Mediterranean world had embedded that concept in their timeless tales.

Think of the tragic, cautionary myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Imprisoned in the labyrinth that he himself had constructed for the tyrannical King Minos of Crete, Daedalus knew that the only way he and his son Icarus could escape was to take to the air on wings. He thus used his legendary ingenuity to construct two pairs of wings that would allow them both to fly to freedom. But he warned his son that in his flight over the ocean, he must neither fly too low, lest the moisture make the feathers of the wings too heavy and drag him down, nor fly too high, lest the sun melt the wax that held the feathers together.

Alas, the impulsive young Icarus did not heed his father's sound advice. As he soared higher and higher toward the inviting sky, the heat of the sun softened the wax, and the feathers, one by one, floated away on the air. Icarus, helpless to stop the process his folly had set in motion, could only cry out in terror as he plummeted downward to his death.

Icarus is not the only impulsive young man to appear in the myths of ancient Greece. Phaethon, when he learned that he was the son of Helios, the god of the sun, asked his father to give him whatever gift he asked for. Helios agreed, only to have Phaethon request that he be allowed to drive his father's chariot of the sun. Unable to dissuade his son from this plan, Helios could only give him advice on how to handle the fiery horses that pulled the chariot. But the advice proved vain, for Phaethon lacked the strength and skill to keep the horses unified and on course. In the end, Zeus was forced to kill Phaethon with a lightning bolt to prevent the madly veering chariot from scorching the heavens and earth.

According to the wisdom literature of the Old Testament, the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom (Job 28:28; Psalm 111:10; Proverbs 1:7; 9:10). When we lose that fear, we fall off course as quickly and tragically as the impulsive Icarus and Phaethon did. A Christian who might struggle to understand what it means to lose the fear of the Lord will likely not find it hard to understand the exact nature of the error that Icarus and Phaethon made by not paying heed to the protective wisdom of their fathers.

These twin myths can help teach Christians a truth that is too often missed by those who are perhaps overly familiar with the Bible: namely, that God the Father lays down rules for us, not to restrict us from enjoying our lives, but to guard us from self-destructive behavior. When we stray too far from the middle course that God has established for us, when we forget that there is a proper time for everything under the sun (Ecclesiastes 3:1-8), we inevitably hurt ourselves and those around us.

What Story Are We a Part Of?

Although the Bible is the only book that Christians need to find salvation in Christ and live a virtuous Christian life, interaction with the myths of ancient Greece can offer helpful insights into the nature of our world and the kinds of consequences that follow in the wake of bad choices and actions. Such an interaction can also help us grapple with the nature of the story that we are a part of. The Bible lays out the parameters of that story—that grand narrative of creation, fall, redemption, restoration, and glorification—but myths read with a discerning mind and spirit can flesh out that story.

Consider the beloved tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, one that has inspired poets, artists, and composers for thousands of years. It all started so well. Orpheus, the king of Thrace and the greatest musician of his age, fell in love with, and won the heart of, the fair Eurydice. But before their honeymoon had ended, a snake bit Eurydice in the ankle, and her soul was taken down to Hades. Orpheus wandered the earth in search of the hidden doorway to the underworld. When he found it, he bravely descended the stairs and came before Hades himself and his dread queen.

When Hades refused to release Eurydice from his realm of the dead, Orpheus played on his lyre and sang so sweetly that iron tears fell from the pitiless eyes of Hades. He granted Orpheus the boon he requested but warned him that he must not look back at Eurydice until she had left his dark domain and returned to the sunlit world. All went well until they approached the final flight of stairs, when Orpheus was seized with fear that Hades had tricked him. To calm his fears, he turned his head backwards to make sure Eurydice was behind him. The moment he did so, a great wind rushed down the stairway and blew Eurydice back into the darkness below.

The story, or, better, the pilgrimage, of the Christian compels him to move ever forward, leaving behind his former life of sin and fixing his eyes on the risen Christ. So did Paul conceive of his own Christian walk: "Brothers, I do not consider that I have made it my own. But one thing I do: forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus" (Philippians 3:13-14). We must not, like Lot's wife (Luke 17:32), look back on the world of depravity from which we have been rescued. Let us not grow weary in our race or allow fear or regret to tempt us to cast a backward glance at our unregenerate life.

The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice puts flesh on the admonitions of Paul to press forward and of Jesus to flee without looking back. It allows Christians who read the Bible too casually and passively to experience the consequences of taking our eyes off of the author and finisher of our faith (Hebrews 12:2).

And it does one other thing. Inasmuch as we identify with Orpheus, we will be called and admonished to press forward in our pilgrimage. If, however, we read the myth a second time and identify with Eurydice, we will realize that our Orpheus has both the power and the purity to harrow hell and rescue us fully from its dark lord. The music he plays saves and restores completely, calling back life out of death.

That is the story of which we are a part. We are the bride of a bridegroom-king who will not fail or leave us to molder in the grave. It is the Bible, not the myth, that assures us of that promise, but the myth, read rightly, can help render that assurance dramatically concrete and vividly real.

Louis Markos(www.Loumarkos.com) is Professor in English and Scholar in Residence at Houston Baptist University; he holds the Robert H. Ray Chair in Humanities. His books include From Achilles to Christ, Apologetics for the 21st Century, and Literature: A Student's Guide.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #55, Winter 2020 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo55/the-epic-struggle-is-real