Good Scientists Think (& Speak) Like Good Theologians

Our culture often portrays science and Christianity as being in conflict. This, I believe, is because too few people really understand what science is. If we, as Christians, had a better understanding of science, we would be able to defend ourselves against accusations of ignorance and would do a better job preparing young people to reclaim the sciences for the faithful.

I have a somewhat unusual background in that I am both a scientist and an engineer. I have a doctoral degree in engineering, and I did post-doctoral work in the medical sciences. I publish more often in the sciences—about two-thirds of my time is spent doing scientific research, while one-third is spent on engineering. Because I have this odd background, I often feel the tension between what science is and what it is not. Scientists approach problems differently than engineers or other scholars do. They follow principles that govern the way they approach problems—principles that must be followed if they wish to have their works published in scientific journals or to receive grants to fund their research.

An Old Conflict That Didn't Exist

Let's start by asking the question, "Are science and Christianity historically incompatible?" There's a very simple answer: "No, not at all." We know, if we go back through history, that most of the famous scientists of Western civilization were Christians and that many were very devout. One can easily find many references to Christianity by famous scientists of previous generations.

For example, Isaac Newton said, "The most beautiful system of the sun, planets, and comets could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being." In addition to being the founder of classical physics, Newton was a theologian, at least in his own mind. He was a terrible theologian, as is evident from his commentary on the Book of Revelation, but I applaud him anyway, for he had a heart for God and at least tried to study theology. In any case, his lack of success as a theologian is beside the point, which is that he considered himself a devout Christian man.

Or consider someone like Robert Boyle, who died in 1691. He is known to every freshman chemistry student for the equation PV = nRT—the gas law. Unfortunately, he is far less known for the time he spent studying theology and writing such works as Some Motives & Incentives to the Love of God and The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of Creation. He also personally endowed an annual lectureship devoted to the defense of Christianity against atheism. Certainly Boyle was a man who cared deeply about his faith.

Many other founding fathers of science were very devout. Michael Faraday (d. 1867) said, "The book of nature which we have to read is written by the finger of God." Faraday discovered benzene and electromagnetic radiation, invented the generator, and was the main architect of classical field theory.

William Lord Kelvin (d. 1907) said, "As the depth of our insight into the wonderful works of God increases, the stronger are our feelings of awe and veneration in contemplating them and in endeavoring to approach their Author," and "Do not be afraid to be free thinkers. If you think strongly enough, you will be forced by science to the belief in God." Kelvin is known for his work in thermodynamics and electromagnetism, as well as for the Kelvin temperature scale.

More recently, Max Planck (d. 1947), a devout Lutheran, said, "Religion and science demand for their foundation faith in God. . . . For believers, God is in the beginning, and for physicists He is at the end of all considerations. . . . To the former He is the foundation, to the latter, the crown of the edifice of every generalized world view." Planck made many contributions to theoretical physics, but his fame as a physicist rests primarily on his role as an originator of quantum theory.

Other examples could be cited to show that, historically, Christianity has always been compatible with science. Only relatively recently (in the past century) has this been questioned, as the prevailing winds in the academy have blown scholars away from the faith. But to say that science and Christianity are incompatible is to display ignorance of the founders of modern science.

Misunderstood Science

I contend that science is poorly understood in our culture. This can be illustrated with examples of the ways in which the media talk about science, which in turn reflect what our culture thinks about science. If you go to Google and type "scientists say" in the search box, you will find links to articles with headlines like these:

•Wine and coffee are good for your gut, scientists say (Russia Today, Apr. 30, 2016)

• Scientists say wine isn't good for you, after all! (MSN, Jan. 26, 2016)

• Scientists say coffee and gin lovers are more likely to be psychopaths (AOL, Sept. 22, 2016)

• Scientists say coffee is so magical it could even prevent liver disease (Grub Street, Feb. 19, 2016)

• Beer is good for you! Scientists say a pint a day is good for your heart (The Telegraph, May 11, 2016)

• Scientists say woolly mammoth will return (AOL, Aug. 26, 2016)

• Do X-men live among us? Scientists say yes. (Care2, Apr. 20, 2016)

• Aliens exist and will be found pretty soon, scientists say (Forbes, May 24, 2014)

• Scientists say the mythical monster the Yeti is real, lives in Siberia (disinfo, Oct. 24, 2011)

• Sea monsters really do lurk beneath the waves, scientists say (The Daily Mail, July 13, 2011)

• Scientists discuss the reality of a zombie apocalypse. Exclusive! (redOrbit, Apr. 9, 2015)

• If a zombie apocalypse happens, scientists say you should head for the hills (Business Insider, Mar. 5, 2015)

• Scientists predict when world will end (Fox News, Feb. 26, 2008)

• Scientists say 2013 flu season to kill "pretty much everyone" (The Kumquat, Jan. 22, 2013)

• Scientists say wearing a beard makes a man a bajilliondy percent cooler (The Chive, July 16, 2012)

One wonders exactly who the scientists are who make such statements. While a few of these headlines are tongue-in-cheek, most are not. That makes it hard to determine what real science is.

Consider this PRI news item from September 12, 2016: "Scientists say an ancient Mayan book called the Grolier codex is authentic." The principal "scientist" referred to is Mary Miller, the Sterling Professor of art history at Yale University. Miller is renowned in her field, and I have no reason to doubt that she did a fine job in authenticating this historical document. But even if she used the latest, most sophisticated instruments to analyze the codex, that doesn't make her a scientist or her work "science," as PRI claims. If an auto mechanic used an engine analyzer to determine the cause of your car trouble and then performed a repair that got your car running smoothly again, would you call him a scientist and his work on your car "good science"? Of course not. Similarly, even if the folks at PRI do not really understand what science is or what scientists are, they should at least know that art history professors are not of their number.

Let's consider a more egregious example. The Washington Post published an article on August 10, 2016, with the headline, "The seas aren't just rising, scientists say—it's worse than that. They are speeding up." In this piece, which is accompanied by a dramatic photo of large waves approaching a city's shoreline, the writer discusses how "climate scientists" have created computer models that predict a rise in sea level due to global warming. Moreover, "predictions suggest that seas should not only rise, but that the rise should accelerate, meaning that the annual rate of rise should itself increase over time."

If true, this is a very bad thing indeed. However, the author goes on to state, "The problem, or even mystery, is that scientists haven't seen an unambiguous acceleration of sea level rise in a data record that's considered the best for observing the problem." In fact, our intrepid reporter goes on to say, "The record actually shows a decrease in the rate of sea level rise from the first decade measured by satellites (1993 to 2002) to the second one (2003 to 2012)." In other words, the data show that the model is wrong, yet the Washington Post's editors published a headline that drew the opposite conclusion because they believe the model more than the data. For them, reality is less important than their pre-conceived notions.

This is not science. In science, one is expected to test his models, and if they are proven to be wrong, he should change them, not just plow forward ignoring contrary evidence.

What Real Science Looks Like

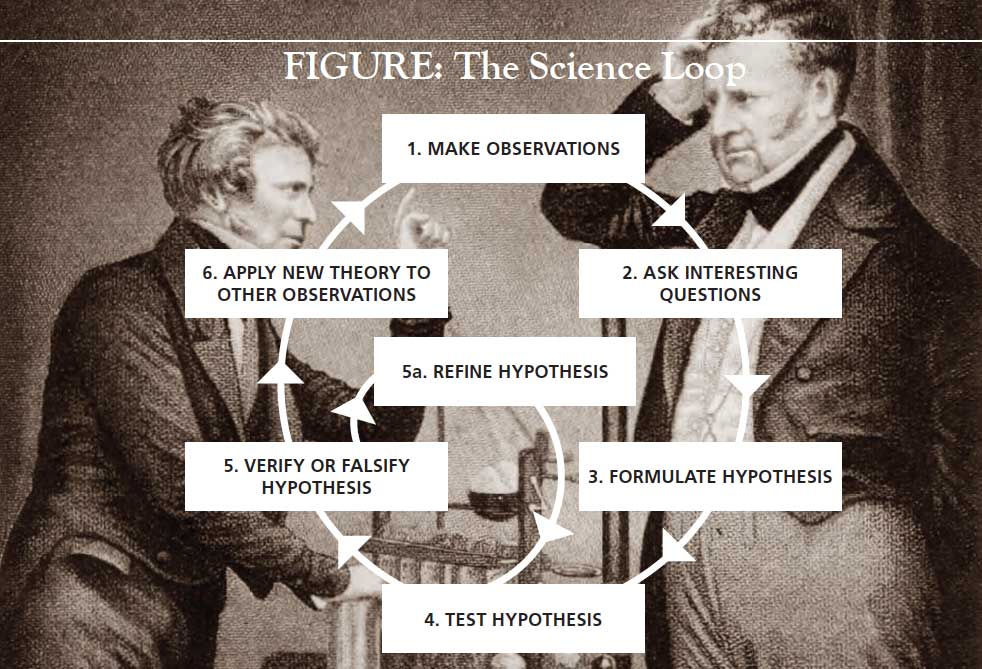

Let us consider what science is supposed to look like. Science can be thought of as a type of loop:

The first step is to make observations: What do I see in nature? The observations can come from my own experiences or from thoughts or readings. The next step is to think of interesting questions, such as, Why does a particular pattern occur? Next, I formulate hypotheses that might explain the general causes of the phenomenon I am pondering. Then I develop testable ways to predict whether the hypotheses are true or not. If a hypothesis is true, I can develop a study that will expect a certain type of outcome. Next, I gather data to test my predictions. This allows me to verify or falsify my hypotheses. If they are shown to be wrong, I can refine, alter, expand, or reject my hypotheses and then go back and develop new testable predictions. If the hypotheses are proven to be true, I can then move forward to develop general theories that are consistent with what I have learned. From there, I begin again, closing the loop and applying the new knowledge to other observations in the future.

This is the way real science is done, following the basic flowchart that outlines the scientific method. If I am doing science, this is what I am doing. If I am doing something else, then I am not doing science.

The fundamental nature of modern science is that it is rooted in having at least one hypothesis that is both (a) important and (b) testable (and repeatable).

Regarding (a), I can, for instance, formulate a hypothesis that the earth orbits the sun and therefore the sun will appear to rise in the east every morning. While that hypothesis is testable, it is hardly interesting because it has already been demonstrated and adds no new knowledge. Such a hypothesis is not important.

Regarding (b), my hypothesis must also be testable or, to use Karl Popper's term, "falsifiable." It must not be just an opinion, but must be able to be objectively verified with quantifiable data that can be demonstrated to be likely to be true within a defined level of statistical tolerance. Furthermore, the hypothesis must be tested in a way that a false conclusion is possible.

Given this understanding of science, I have never encountered a scientific hypothesis that conflicts with Christianity. I have encountered some scientific studies that are unethical, but that is a different thing. Unethical studies may be formulated to enrich the scientist or to bring harm to others if the studies are done. But the hypotheses themselves do not conflict with the faith.

Why, then, do we hear so much about a conflict between faith and science? Mostly because we do not properly understand science. Most examples of this conflict do not involve scientific studies, that is, studies with scientific hypotheses. Take, for example, the idea that the various living species came about through evolution. That is not a testable hypothesis. Rather, it is an approach to studying the history of creation so as to develop ideas about the origins of creatures and objects within it. Right or wrong, true or untrue, such study is not science per se.

Science is based on educated guesses that can be verified. I think Michael Polanyi stated this very well when he wrote,

The propositions of science thus appear to be in the nature of guesses. They are founded on the assumptions of science concerning the structure of the universe and on the evidence of observations collected by the methods of science; they are subject to a process of verification in the light of further observations according to the rules of science; but their conjectural character remains inherent in them. As I am convinced that there is a great truth in science I do not consider its guesses as unfounded. (Science, Faith and Society, 1946, 31–32)

Note that science is different from engineering. Engineers are great at creating things. An engineer asks himself, Wouldn't it be cool if I built a wristwatch that had a blender on it? Then he goes into his laboratory and makes one. He is smart and clever, but he is not a scientist because he does not use a scientific approach. He does not ask scientific questions (i.e., he does not bother formulating testable hypotheses). He is an applied scientist—he uses science to make new things. What often passes for science in our culture is really engineering or applied science. But while these are good and interesting fields, they are different things from science.

Opinions versus Tested Hypotheses

I once read a news article that began, "A report in the scientific journal Deviant Behavior states. . . ." My immediate reaction was to ask how there could be a scientific journal with that name. I looked at some of the articles in that journal and saw nothing that used scientific methods to test hypotheses related to biology or behavior. The contents were rubbish, not science. Yet because the writers in that publication claim to be doing science, they are given carte blanche by our culture.

Science is terribly misunderstood. Take a topic that is popular today: global warming. This topic has a testable hypothesis: that the world's average temperature is increasing. However (at least according to some), the data gathered to support this hypothesis show that the earth is not necessarily getting warmer. As a result, the hypothesis has been renamed "climate change." But the hypothesis that the weather will change from day to day is not scientific, as it is neither important nor interesting. Of course the weather changes every day!

What is actually meant by "climate change" is that man-made pollutants have caused significant and substantial changes in the world's climate. That is an interesting hypothesis. But, as far as I know, no studies have been proposed that would determine: (a) how much of any particular weather change can be attributed to man, or (b) whether any specific changes in human activity would have a mitigating effect on such climate change.

Instead, the approach employed to study the question involves the use of computer models. It has been observed that computer models that include parameters for man-made pollutants are better predictors of the weather than those that don't, and it is believed that future weather will look better if such pollutants are minimized.

This is not really "science," but a type of mathematical curve-fitting. I do a lot of mathematical modeling in my own research, and I know it is a legitimate way to study things, but that doesn't make it science. If someone has great confidence in the accuracy of climate-change models, he may well believe that man-made pollutants must be minimized to avoid future weather-related catastrophes. If he lacks confidence in the models, he'll more likely believe that the predictions of disaster are overblown. This is the heart of the climate-change debate, and much name-calling has gone back and forth between those who believe in the accuracy of the models and those who don't.

This is actually rather odd, because I know of no other topic on which people's opinions are based on their belief in the accuracy or inaccuracy of computer models. Now, I am not saying that computer models of climate change are valid or invalid; I am just pointing out that this is indeed what people are talking about when they argue about "climate change." Do you believe in the predictive capacity of these models or not? That is what it boils down to.

I deal with computer models of nonlinear dynamic systems and understand that they can be very complicated, far more so than the average scientific layman realizes. Perhaps it is for this reason that St. Augustine said, "The good Christian should beware of mathematicians and all those who make empty prophecies. The danger already exists that mathematicians have made a covenant with the devil to darken the spirit and confine man in the bonds of Hell" (De Genesi ad Litteram, II, xvii.37). I show this quote to my Ph.D. students who are doing computer modeling, and I am sympathetic to those who make computer models, for it is not easy to make convincing ones. But that doesn't mean that I trust their models. As we saw with the models mentioned in the Washington Post that predict the rising of the seas, they are not always terribly accurate.

Thus, there is very little "science" in "climate science," and until this is understood, talk about what "scientists" believe about such things is meaningless. Most of what we read today from "scientists" is not really science, just opinion (and often politics). Moreover, even when an actual scientist expresses an opinion, it does not mean he did a scientific study to verify it. All scientists have opinions, but not all do good science to prove their theories. Scientists in general are opinionated people, as are many others, especially those with Ph.D.s in any field. But having opinions is not the same thing as doing good science. The phrases "scientists believe . . ." and "scientific studies have demonstrated . . ." are two very different things. Opinions are different from conclusions derived from actual scientific studies.

Jonathan Swift famously said, "You cannot reason a person out of a position he did not reason himself into in the first place." This is a problem with what passes for modern science in the press. It is dogma wrapped in a scientific veneer. The underlying dogma comes from political or philosophical views of the universe, which may or may not be correct. Whether or not such positions are true is often irrelevant to those who hold them dearly.

Real science should be based on hypothesis-testing, not a priori dogma. There is nothing in the former approach that contradicts the faith because real science is the study of a universe that has been created by God. As the Psalmist says, "I muse on what thy hands have wrought." That should be the role of science.

Reclaiming Science

Good scientists think like good theologians do: they believe in universal truth—that what holds true in the lab is true in the world. This is good thinking. Hence, they ought to make good allies for Christians.

We need to train Christian scientists, starting when they are young, teaching them what is real science and what is nonsense. We should also teach students not to venerate scientists, but to respect science and seek after truth, in natural laws as well as theological ones.

In the Middle Ages, one's education began with the trivium, which consisted of grammar, logic, and rhetoric. Once these were mastered, the student was ready to begin the more advanced topics of the quadrivium: music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. Only when he had mastered all seven liberal arts of the trivium and quadrivium was the student considered competent to proceed to theology. The ancients realized that the arts and sciences were subordinate to God, and only the best minds were allowed to be trained in theology.

In our world, theology has taken a back seat to science, but only because we have allowed it to. It is still a much more difficult thing to understand—the workings of the Lord of the universe—and although many excellent scientists are working today, I know of few world-class theologians. I believe this is because theology requires an understanding of many fields—history, philosophy, literature, science, and so forth—while science is far more narrow, requiring specific technical skills and little knowledge of anything else. Most of the scientists I know do not have the skills to study theology.

American culture advocates many nonsensical ideas that it thinks are rooted in science: the notion that a human being is not a person until he is born; the idea that human beings have not just two sexes, but over 50 genders; the existence of aliens, x-men, zombies, and "gay genes"; the idea that the world will end soon and that salvation can only be found in governmental regulations. Such notions are not rooted in science—they are profound silliness!

The real world—the Christian world—is not so. We know that the secrets of the universe can be found through knowledge of him who made everything. What scientists study is God's creation. What they seek is truth. Is this not a noble calling for a young person? Is this anything that should conflict with our faith? Of course not!

We have nothing to fear from the honest scientist, just as we have nothing to fear from truth. What we need are more honest scientists who are Christians and are not afraid to proclaim their faith, showing the world that the so-called conflict between faith and science is false and that honest science can be done by those who love Christ.

Thomas S. Buchananholds the rank of fellow in four professional societies, has served as editor-in-chief of a scientific journal, and frequently reviews medical research grants for federal agencies. He is also a senior editor of Touchstone.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #50, Fall 2019 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo50/the-soul-of-science