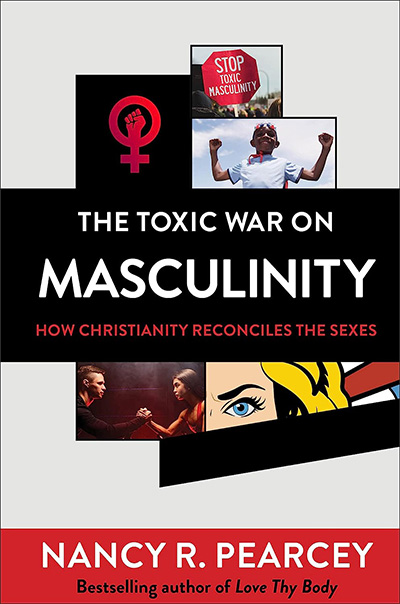

Nancy Pearcey on What Happened to True Masculinity, and How We Might Get It Back

For those not familiar with Pearcey’s writing, I’d suggest reading this short introduction I wrote to her other major books. Her new book follows a similar approach of taking on a controversial topic through an interdisciplinary lens. Pearcey knows her way around history, social science, philosophy, theology, and Scripture, and this allows her to weave together arguments and sources that frequently are kept separate. And this approach oftentimes sheds new light and fresh insight on topics that can seem well-worn or predictable in their patterns of argumentation. Below are a few snapshots from the book where the benefits of Pearcey’s approach are on clear display.

Tackling Contemporary Stereotypes: The “Good” Man and the “Real” Man

She begins by laying out two competing life scripts for masculinity—the “good” man and the “real” man, both of which, research has shown, have wide purchase as general concepts in cultures across the globe. In general, the “good” man is understood as one who exhibits “honor, duty, integrity, sacrifice.” Contrastingly, to be a “real” man in many cultures today is to “never show weakness, win at all costs…get rich, get laid.” Pearcey notes, “men everywhere seem to experience tension between what they themselves define as the good man and the way the surrounding culture pressures them to be a real man.” As Pearcey sees it, “the problem with the stereotype of the ‘Real’ Man is that it is one-sided. When separated from a moral vision of the Good Man, it can easily degenerate into sexism, dominance, entitlement, and contempt for those perceived as weak—traits we can all agree are toxic” (19).

Disambiguating Committed versus Nominally Christian Men

Pearcey then challenges one of the common stereotypes about conservative Christian men: that they are demeaning towards women and that their theology justifies mistreatment of women. Pearcey documents this claim’s frequency in pop culture and mainstream media, but then marshals extensive social science research to show that “evangelical Protestant men who attend church regularly are the least likely of any group to commit domestic violence.” It is nominally Christian men, those who claim Christianity as a label but rarely if ever attend church, who have the highest rates of divorce and domestic violence. All of this means that “any statistic that blends together both committed and nominal Christian men will be misleading” (37).

Pearcey then offers her perspective on why this divergence between nominal and committed Christian men emerges when it comes to metrics of family flourishing.

It seems that many nominal men hang around the fringes of the Christian world just enough to hear the language of headship and submission but not enough to learn the biblical meaning of those terms…. They cherry-pick verses from the Bible and read them through a grid of male superiority and entitlement that they have absorbed from the secular guy code for the “Real” Man. (37)

After laying this groundwork, Pearcey then goes on to trace the trajectory of masculinity through several centuries, starting roughly in the colonial era. But there is one shift that was particularly definitive in changing the role of men and the conception of home, work, and family that still has us reeling today, and continues to form much of our patterns of thinking and living.

The Industrial Devolution

Through close analysis of primary sources and historical developments, Pearcey argues that the Industrial Revolution led to drastic changes in family life. Living our lives on this side of industrialization, it is hard for us to even imagine how different life was prior to its inception. Frequently, we unknowingly assume our current, post-industrial economic, educational, and familial arrangements as timeless norms. But as Pearcey wittily puts it,

When people talk about restoring the “traditional” family, typically they are not being traditional enough. Often they are thinking back to the 1950s. But they should think back to the pre-industrial age (which includes most of human history)—a time when both fathers and mothers combined childrearing with economically productive work. (225)

This is a very important point, one that frequently gets overlooked. For most of human history, life was structured much differently than what we presume as normal for industrial and post-industrial societies. For one, most adults—men or women—didn’t go to work in the way we conceive of it today. Economic productivity in prior times was much more connected to one’s home and family, and it ebbed and flowed naturally with the seasons. Mother and father spent more time with their children in the warp and woof of pre-industrial life, and their educational and economic ventures were joint projects. There was “an integration of life and labor,” Pearcey notes. “Husband and wife were engaged in a common enterprise (though not necessarily identical tasks). They worked side by side, suffering common defeats and rejoicing in common victories. A husband/father was the head of a small commonwealth—a semi-independent economic unit” (72).

Industrialization, however, drove a wedge between home and work, family and father. Pearcey laments, “because men were gone from home most of the day, they began losing out on dimensions of their personality that were no longer being fostered by deep relationships within the family” (92). Work increasingly became man’s domain, separate from women and children and, as such, a new set of self-interested and utilitarian principles came to dominate in the workplace.

Meanwhile, the women and children who worked in factories or mines were now treated as isolated economic units or replaceable parts, rather than members of a coherent family working towards a shared goal. No longer were love and a vision of the “common good” driving economic decision-making; now profit and productivity took center stage. This is not to say that profit and productivity are bad or have no place; but that there is substantial risk when they are untethered from higher virtues or disconnected from family and other communal structures.

All of this means we must go further back than the past few generations, second-wave feminism, and the Sexual Revolution to get a full picture of what has happened to family structure and gender roles. We must be willing to go deeper, and Pearcey leads the way.

For Further Exploration

Of course, much more could be said regarding these brief snapshots from the book. But I hope they whet your appetite for reading the whole thing. I know this may seem like hyperbole, but there is something in this book for everyone—it’s that good. There are countless new insights and nuggets for understanding our past and present and helping us navigate life as men or women at any stage of life. Here are a few more of the nuggets that struck me most:

Darwinism’s Impact on Masculinity

Pearcey traces Darwinism’s impact on masculinity—how it became an excuse for sexual infidelity, aggressiveness, and survival of the fittest behavior in men, and how in more recent forms of evolutionary psychology, it painted men as needing to be tamed by women and marriage. Against Darwinian conceptions of masculinity, Pearcey argues, “men do not have to sacrifice their essential identity in order to marry and raise a family” (169).

The Shaky Doctrine of the Separate Spheres

Pearcey also takes an in-depth look at the 19th-century development of the metaphor of two spheres—that there was a domestic sphere for women, and a public sphere for men. This concept was closely associated with the cult of domesticity, which, ironically, was a response to industrialization’s fragmenting force, which accentuated the division between home and work, women and men, faith and everyday life. Pearcey argues that “the ideology of domesticity was really a form of sentimentalism—it gave people the opportunity to profess devotion to ethics and morality very convincingly, without actually changing or challenging any of the secular worldviews that were shaping the world of politics and economics.” She continues, “as morality was privatized, men were relieved of the responsibility to apply a Christian worldview in the public realm…[as] the definitions of both male and female character became narrower and more constricted” (108). The church itself bought into this division and began to see the woman as the ideal religious figure—that women were naturally religious while men had to be trained into religion. And the ramifications of these skewed understandings of men and women are still being felt today.

Hope for the Future

Yet Pearcey is not one to leave her readers without any hope. Throughout the book, the pictures she paints of what family life can be from a biblical and historical perspective are inspiring, and the brief snippets of contemporary families charting new (and old) paths in restructuring work, home, and family life offer concrete ideas. She sees in our post-industrial age an opportunity to renegotiate and reconsider family and work arrangements. “It was the industrial economy that drove men out of the home; it could be the post-industrial economy, with its advanced technology, that will bring men back” (216).

Her closing lines offer a fitting conclusion here: “masculinity is not originally or intrinsically toxic. Duty and compassion are masculine virtues, integral to male character. True masculinity is a good gift from God, and we should be grateful for the men who embody it” (270).

Joshua Paulingis headmaster of All Saints Classical Academy and vicar at All Saints Lutheran Church (LCMS) in Charlotte, NC. He also taught high school history for thirteen years and studied at Messiah College, Reformed Theological Seminary, and Winthrop University. He is author of Education's End and co-author with Robin Phillips of Are We All Cyborgs Now? He also has written for Front Porch Republic, Mere Orthodoxy, Public Discourse, and Touchstone.

• Get SALVO blog posts in your inbox! Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/post/the-descent-of-man