A Reflection on Visiting the House of Mourning

Grief does not want to be read about as much as it wants to be written about. Books about grief weigh more than other books; they ask you to turn stiffer pages and decode heavier words. Their gravity must be borne throughout the book’s reading and after its completion. Whereas every day comes with plenty of trouble, why cumber ourselves with this additional load of care?

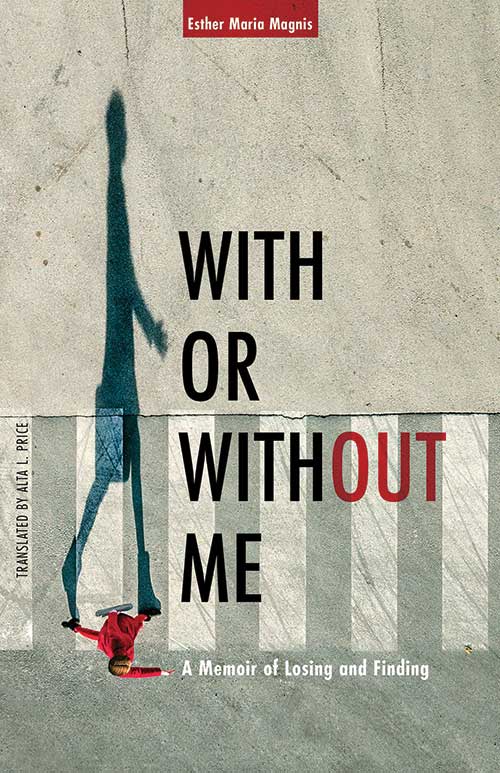

For me, let’s just say it’s because someone recommended With or Without Me, by Esther Maria Magnis. That recommendation was a gift of grace, however little I was inclined to read another book about grief.

Esther’s story is not unique. Her dad is diagnosed with terminal cancer while she is a teenager. Esther and her siblings have grown up in a religiously mixed German household (Roman Catholic mom, Protestant dad) amid 1980s feel-good pieties. The liturgical colors of German ecumenism are red and yellow, black and white, accented with lots of green.

The kids are not convinced. What’s the use of a church that just tells you the same things you hear everywhere else, where the only sin is racism and the highest good is recycling? Why go to services whose intent is to make you “care,” but whose effect is to make you cringe?

Even so, God moves in a mysterious way. The drivel Esther and her brother and sister have been fed in theologically gutted churches drives them to forage for real promises and real comfort in the Word that endures forever. They band together after their father’s diagnosis in prayers offered surreptitiously in their attic. In Esther’s agony of fear and desperation, the seeds of the gospel that have been cast on her young heart take root. She grasps with both hands the crisis her brother articulates: “To know you’re going to die . . . we’re just not made for this.” What is harder to believe? That a human being can simply cease to be, or that God is real, loves, and saves?

Those for whom the latter proposition is inadmissible must reckon with the fallout. The deceased are reimagined as ghosts, or kept alive in our hearts. How a ghost could be of any value, or memory in another mortal heart could be considered compensatory, is unclear. The wide acceptance of such shoddy jerry-rigging of the human race’s existential calamity is nearly as mysterious as divine grace.

The Gift of Mourning with Those Who Mourn

Grief is an abstraction, but it doesn’t act like one. It muscles its way into being known and understood. The grieving need to introduce this presence that has taken over their lives to those around them. Grief acts like a muse, drawing expression from people who have previously been a-mused. When life no longer diverts and entertains, explanation is needed. This is why the unwilling participants in tragedy find themselves suddenly talking, writing, drawing, composing, expressing.

Those who are neighbors to the victims of tragedy usually do not know what to say. “Thoughts and prayers” is the formulaic reduction of all the love and empathy that cannot be stated, and the formula’s shortcomings are well known. But one treatment is built into the problem: rather than saying something, the empathetic neighbor can receive what grief generates in the minds and hearts of the bereaved. The neighbor can invite and welcome the work of mourning’s muse. The neighbor can wait in silence, sit with, listen, and hear. The neighbor can learn the anatomy and physiology of a loved one’s grief—its habits, fodder, and weak points.

Although grief looks and behaves in ways as different as every individual, it is always the same kind of beast. It is huge and mighty, but it must be domesticated so that the mourner’s life can be tolerated. Yet, not all ways of managing grief are as wise as others, which is why Esther’s testimony in With or Without Me is so valuable. In earlier life, Esther had unintentionally collected a number of providentially laid tokens. These became her life preservers after her father’s death. A private brush with the sublime; her familiarity with the house, Word, and things of God; a snatch of a song of faith—all these were hidden in her heart for the Spirit to bring forth in her hours and years of deepest need.

Most people possess a few things like this. Life seeds us with accidents that, when the wages of sin are demanded, may grow into revelation and miracle. If they are doubted, twisted, rejected, or mocked, our dear departed ones become to us worthless ghosts and memories. But the seed-grains of help strewn throughout our personal histories can be recalled to mind, clung to in faith, illuminated with hope, and vitalized by the power of the gospel. These snatches of the kingdom of God can be brought forth so that every good and gracious gift may be added unto them: endurance, trust, peace. Rest, redemption. Forgiveness. And eventually, Resurrection.

On Surrender

Esther’s story, again, is not unique. This is why one might shrink from her book. To touch it is to acknowledge grief’s reality, to open ourselves to that huge and mighty beast we dread so much. But in opening to it, we also open ourselves to those who suffer. We make ourselves available to people living in its shadow. We become more able to offer whatever help there is for them, the help we say we wish we could give.

Grief always brings temptation. Bereavement is an open pit of doubt and despair, but Esther testifies to how the Lord provided a way out for her, and in so doing, she confirms what faith suspects: every scrap of the Word rattling around the keening mind is there for a reason. And it is the answer. Knowing this and having some understanding of grief’s character situates us to give what aid we can to those suffering its power.

Studying grief can never be academic. Neither can it be oriented entirely outward. Anyone who has received the holy gift of love will also feel the demonic anguish of loss. Semper paratus, Christian. It behooves us to hear the faithful, to learn good from good, to sojourn where Wisdom has visited and redeemed His people. Jesus wept to show us how.

But a Jesus who is only an example is as useless as a church dressed in the same colors that fly in the public square. The only God who is worth anything is the God who would not let those he loved become ghosts and memories. The beast is huge, but not infinite; it is mighty, but not almighty. There is one Infinite, one Almighty. There is the God who knows grief because he grieved, the God who knows death because he died, the God who gives life because he lives. “In no other religion does faith entail such lofty claims, or demand as much as it does of Christians, whose God supposedly ended up on a cross,” Esther says. Verily, the only thing harder to believe than that any one of us should die is the idea that God should.

So even those seed-grains of miracle are no more than life preservers. Only the Word can revive the spirit that has taken on too much grief. The Lord prayed on our behalf, “Sanctify them in the truth; your word is truth” (John 17:17).

“Truth is God, and therefore so implacable that it hurts to push against it,” Esther observes. “Its sheer density shatters everything, because it’s more real than anything else.” What then shall we say to these things? “All you can do,” writes Esther, “is get down on your knees before it.”

Rebekah Curtisis coauthor of LadyLike (Concordia 2015). She has written for a variety of websites, magazines, and books. Her day job is housewife, church lady, and school mom.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #64, Spring 2023 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo64/reckoning-with-the-grave