Make Sure You Know Where to Look & How You Might Miss It

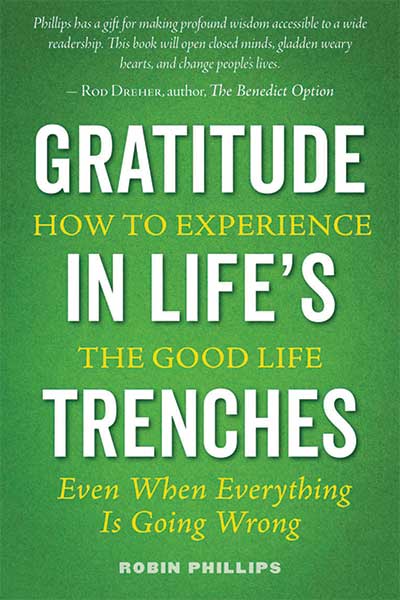

There is no shortage of books exhorting the discontented soul with endless clichés to embrace positive thinking. One might be inclined to regard Robin Phillips’s Gratitude in Life’s Trenches: How to Experience the Good Life Even When Everything Is Going Wrong (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2020) as just another one of those books. However, far from a feel-good treatise, Phillips’s book offers a rich synthesis, drawing from biblical principles joined to timeless wisdom from thinkers spanning a wide range of backgrounds, professional domains, and eras.

Phillips brings together the latest research in cognitive behavioral psychology with the rich contributions of church fathers—ancient and modern, Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. This framework is buttressed by examples of people from history and literature, and by personal stories (including his own). What emerges is a highly textured composition that focuses on learning how to express gratitude when life is most challenging and how to experience the good life when everything is going wrong.

Paradoxical

The reader will learn that the good life is often paradoxical, as it involves: finding joy when giving up the pursuit of happiness; engaging in proper self-care in order to forget about oneself and care for others; expressing gratitude while in the midst of life’s greatest challenges; and drawing strength from God by acknowledging our own human frailty.

Phillips’s respect for his readers is manifest in his recurring motif that there are no quick fixes to the good life; rather, it is process-driven, requiring both patience and time. He acknowledges that life is just plain tough at times. As frail creatures suffering the effects of the Adamic fall, we often see life as promising little more than times of pain, suffering, and disappointment; accordingly, there is no silver-bullet solution to living a good life.

Counterintuitively, it is the search for happiness that leads to greater discontentment. Phillips cites research by Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert, who set out to ascertain the ingredients that comprise a fulfilled life. Gilbert and his colleagues characterized two types of happiness: “natural happiness” (the consequence of getting what you want), and “synthetic happiness” (the happiness you make for yourself in the face of disappointment—largely attitudinal). Gilbert’s research revealed that it often takes deprivation in natural happiness to generate synthetic happiness and that a life of ease and comfort often undermines a life of meaning.

The good life then, is about finding joy that comes when we give up pursuing happiness and pursue meaning instead. Having studied the lives of people who lived and survived conditions of absolute misery, what Phillips discovered is that attitude was key. The things we can control in our internal environment are more fundamental to achieving this good life than the things we cannot control in our external environment.

Citing the writings of Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, a survivor of the Nazi death camps, Phillips points out that finding meaning in hard circumstances involves both attitude and decision—that what is important is possessing a “will to meaning,” which involves “the determination to find meaning, purpose and significance through situations that might otherwise lead to hopelessness and depression.”

This search for meaning entails being realistic concerning the conditions of suffering, while seeking out a higher purpose. This higher purpose is often realized when we can forget about ourselves in the service of others. Far from the fragile “true self” that modernity proposes, Christianity teaches that our true selves are found by setting aside our own self-interest and giving ourselves away to serve the needs of others.

Spiritually Profitable Suffering

Pointing to the examples of the apostles Paul and James, who exhorted their readers to rejoice in their various trials, Phillips reminds his readers that such expressions of thankfulness are not rooted in sentimental optimism. Instead, these attitudes accompany coming to terms with one’s own weakness, thereby enabling God’s strength to become fully manifest.

Indeed, the truly good life is often unearthed during times of suffering. Phillips quotes the Jewish Catholic writer Léon Bloy: “Man has places in his heart which do not yet exist, and into them enters suffering in order that they may have existence.” He adds: “when a person’s external world becomes unusually restricted, that person is forced to realize resources available within his own heart—resources he may not have realized if his life had remained easy and without suffering.”

Phillips challenges his readers to actually lean into their pain for spiritual growth. Suffering often brings us to a fork in the road whereby we can either feel sorry for ourselves or channel our suffering into effectual prayer and service for others. A wrong response to pain can inadvertently assist the devil in our own affliction. We must “choose whether our emotional pain will yield spiritual profit, or whether it will simply go to waste.”

Phillips advocates the patient development of several key virtuous habits, conceding that, in the beginning stages, these habits may feel strange and inauthentic—but the more they are practiced, the more natural they will become. These habits include, but are not limited to: a retraining of one’s outlook on life; learning to reframe situations in our lives in the context of God’s promises; developing practices of gratitude (even when we do not “feel” thankful); and most powerfully, cultivating what is called a “sacramental imagination.” Contrary to what modern secular materialism seems to be teaching, this sacramental imagination, informed by a fully Christian worldview, is centered on faith in Christ, in whom “all things hold together.” And that includes the material cosmos and everything in it.

The modern alternative is to find meaning in the self. These two worldviews couldn’t be farther apart. Only one of them can be right.

Emily Moralesgraduated summa cum laude from California State University, Fresno, with a BS in molecular biology and a minor in cognitive psychology. As an undergraduate, she conducted research in immunology, microbiology, behavioral and cognitive psychology, scanning tunneling microscopy and genetics - having published research in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, and projects in scanning tunneling microscopy. Having recently completed an M.Ed. from University of Cincinnati and a Certificate in Apologetics with the Talbot School of Theology at Biola University, Emily is currently an instructional designer/content developer for Moody Bible Institute and teaches organic chemistry and physics. As a former Darwinian evolutionist, Emily now regards the intelligent design arguments more credible than those proffered by Darwinists for explaining the origin of life.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #63, Winter 2022 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo63/want-a-good-life