Peter Ustinov's "Billy Budd"

To make a masterpiece, it's not enough that you have ambition, intelligence, and even technical skill. The seed must fall on good soil, not concrete. Some boy may walk among us who would have been Mozart in Salzburg in the eighteenth century, surrounded by music of extraordinary variety, beauty, and power. But we do not know him, because he is playing video games—when he is not daydreaming and getting poor grades in school. If he goes to Mass, he does not hear and commit to memory Allegri's Miserere. He hears music that aspires to the condition of a commercial jingle.

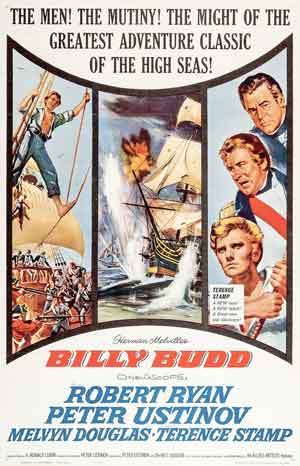

In 1962, when the golden age of film in America and England was drawing to an end, Peter Ustinov adapted Herman Melville's Billy Budd for the screen. He wrote the script for it, he produced it, he directed it, and he played the crucial part of Captain Edward Vere, a sad man who must speculate on the lot of fallen man in a world that punishes innocence.

Ustinov came from that generation of men who fought, by the millions—rich and poor, college boys and mill workers and farmers—in the Second World War. No common experience uniting men has taken place since. Those men knew what it was to worship God in a community, even if, like Ustinov, they turned away from it. Their hands and backs knew what hard physical labor was like. They had grown up without television, and without a glut of trivial and stupid books. Sheet music sold more than did vinyl records until around 1960. Color had not yet supplanted black and white film, so that you could make films that were ideal for that medium, with its intense focus upon the human face.

Ustinov's film could not be made now. Any attempt at it would be full of pretty boys in fancy-dress, mugging and posing to look like sailors. And there would be a Political Message.

Innocent & Doomed

Billy Budd is an unlikely choice for a film. The novella is spare in action and in characterization. The story is quickly told. A handsome young man, Billy Budd, is impressed into service on a man-of-war. He is innocent, brave, and beautiful. Nude, says Melville, he could have posed as Adam before the Fall. He takes to the riggings as a bird to its nest. He wins the hearts of his fellow sailors by his good cheer, his willingness to work, and his freedom from guile or meanness.

But Claggart, the master-at-arms—the ship's disciplinarian—looks on him with envy and suspicion. "Handsome is as handsome does," he says with a cold smile, when Billy by accident spills his soup and a stream of the broth touches Claggart's shoes as he is walking by. Billy thinks it is a sign of his friendliness to him. But a wise old sailmaker, called the Dansker, warns him—the master-at-arms is aiming for him, to destroy him.

Claggart tries to use his flunky, "Squeak," to inveigle Billy into a supposed mutiny, and to spy on him and catch him up in minor offenses against order. But Billy does not bite. Here we first see the tragic debility that brings doom upon him. When he is highly wrought, Billy loses the capacity to speak. He stutters, and in extreme excitement the stuttering collapses into speechless confusion.

The failure does not stop Claggart in his headlong pursuit of evil. He accuses Billy of being the ringleader of a brewing mutiny. When Captain Vere calls Billy to his cabin to confront Claggart's accusation, Billy can say nothing—his words choke in his throat, and his only response is to swing a mighty fist at Claggart's head. The master-at-arms falls, lifeless.

Melville spends the last chapters of the novella examining the cruel problem facing the captain. Vere comes to love Billy as a father loves his son. He understands that the boy is innocent: he had no intent to kill. But as captain of the ship—and in an age, Melville is careful to remind us, when mutinies had rocked the English navy—he must follow the law. Justice is one thing. Law is another. Without law, there could be no navy. The men must not be given a precedent. Isaac must be sacrificed.

I will refrain from describing the final scenes.

Hanging in the Balance

What Ustinov does to transform the novella into a script is nothing short of brilliant. He loses nothing of Melville's nervous examination of "the mystery of iniquity." But a philosophical quandary is not a drama. Melville says that the men loved Billy, that he had an unconscious power to win men's souls; Ustinov shows it. Melville tells us that Claggart was something of a combination of Puritan, Pharisee, and sadist, but he does not give us the struggle between his dominant evil and his still-living apprehension of good. Ustinov does.

Ustinov often solves two or three problems at once, apparently without effort, so that you will feel sure that such a scene must have appeared in the novella, though it did not. The prime example is a night conversation at the side of the ship, between Billy and Claggart. Billy, played by a preternaturally handsome Terence Stamp, is the only man aboard who still thinks well of the master-at-arms after it seems that Claggart, by his severity, has caused the death of a fellow seaman.

We see the two men's faces as they lean over the edge, among flashes of light reflected from the water. Claggart is not ugly. Robert Ryan, one of Hollywood's subtlest villains, tall, lantern-jawed, cerebral, powerful—see him in Crossfire, Bad Day at Black Rock, and Miss Lonelyhearts—is Claggart.

"Why did Jenkins die?" says Claggart, probing, hoping to rouse enmity in Billy.

"You did not wish his death."

"No, I did not."

"You didn't even hate him," says Billy. Then, with the innocent perspicacity of a child who means no ill and cannot imagine that others do, he extends to Claggart a lifeline. "I think," he says, "that sometimes you hate yourself. I was thinking, sir, the nights are lonely. Perhaps I could talk with you between watches when you've nothing else to do."

"Lonely. What do you know of loneliness?"

"Them's alone that want to be."

"Nights are long. Conversation helps pass the time."

"Can I talk to you again, then? It would mean a lot to me."

"Perhaps to me, too."

A human soul hangs in the balance. It is Claudius, king of Denmark, falling to his knees, attempting to "try what repentance can." It is Satan, beholding the sun, with none of the other fallen angels near him, admitting his guilt, and saying, "Is there no place / Left for repentance, none for pardon left?" Something like a smile shows on Claggart's face; and no actor could beat Robert Ryan at flashing something like a smile. But the face hardens. Billy is the tempter here, holding forth the apple of innocence.

"Oh, no. You would charm me too, huh?" says Claggart. "Get away!"

A Trial for Everyone

Why did Claggart bear malice to Billy? The officers sitting at the court-martial in the captain's cabin want to know, since Billy bore no malice to him. Who can say? Someone suggests that the Dansker, who is closest to Billy, may know.

So they call him below. In the novella, the Dansker is a laconic old man who gives Billy the nickname "Baby," and who sees into Claggart's malice. Ustinov's script turns him into a fully realized character, with a presence that commands honor from the younger officers. He is played by Melvyn Douglas, a Hollywood star and sometime leading man for about thirty years; yet here the actor vanishes into the character, and all you see is an old Danish tar, who has seen and known much of sadness, and who carries a small copy of the Bible with him, upon which he swears to tell the truth. Billy is present, but they do not tell the man what has happened.

Was there malice between Claggart and Budd? "Aye," says the old sail-maker, surprising the officers, who look and listen with quiet intensity. "The master-at-arms bore malice toward a grace he could not have. There was no reason for it," he says, and the camera turns toward Captain Vere, whose eyes fall as he bows his head, "that ordinary men could understand. Pride was his demon, and he kept it strong by others' fear of him."

The Dansker speaks slowly, with the clarity of a man who should have been a prophet, almost as if he is explaining things to himself. "He was a Pharisee, among the lepers," he says, patting the cover of his Bible. "Billy could not understand such a nature. He saw only a lonely man—strange, but a man still, nothing to be feared. So Claggart, lest his world be proven false, planned Billy's death."

Now comes what we do not expect at all: it is the sail-maker's moment of trial, and by implication a trial for everyone listening. They are about to dismiss him, when he says, "One thing more. Ever since this master-at-arms came aboard, from who knows where, I have seen his shadow lengthen along the deck, and being under it, I was afraid. Whatever happened here," he says, turning a kindly eye to Billy, "I am in part to blame."

Don't suppose that Billy Budd is a talky film. It is filled with action on the sea. The actors who play the sailors do not seem like actors at all. It is in its own genre a masterpiece, as Melville's novella was. Christian artists in general can learn from Ustinov a great deal about the power of sobriety and judicious understatement—and how not to solve a mystery.

Anthony EsolenPhD, is a Distinguished Professor at Thales College and the author of over thirty books and many articles in both scholarly and general interest journals. A senior editor of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, Dr. Esolen is known for his elegant essays on the faith and for his clear social commentaries. In addition to Salvo, his articles appear regularly in Touchstone, Crisis, First Things, Inside the Vatican, Public Discourse, Magnificat, Chronicles and in his own online literary magazine, Word & Song.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #59, Winter 2021 Copyright © 2026 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo59/the-moment-of-darkness